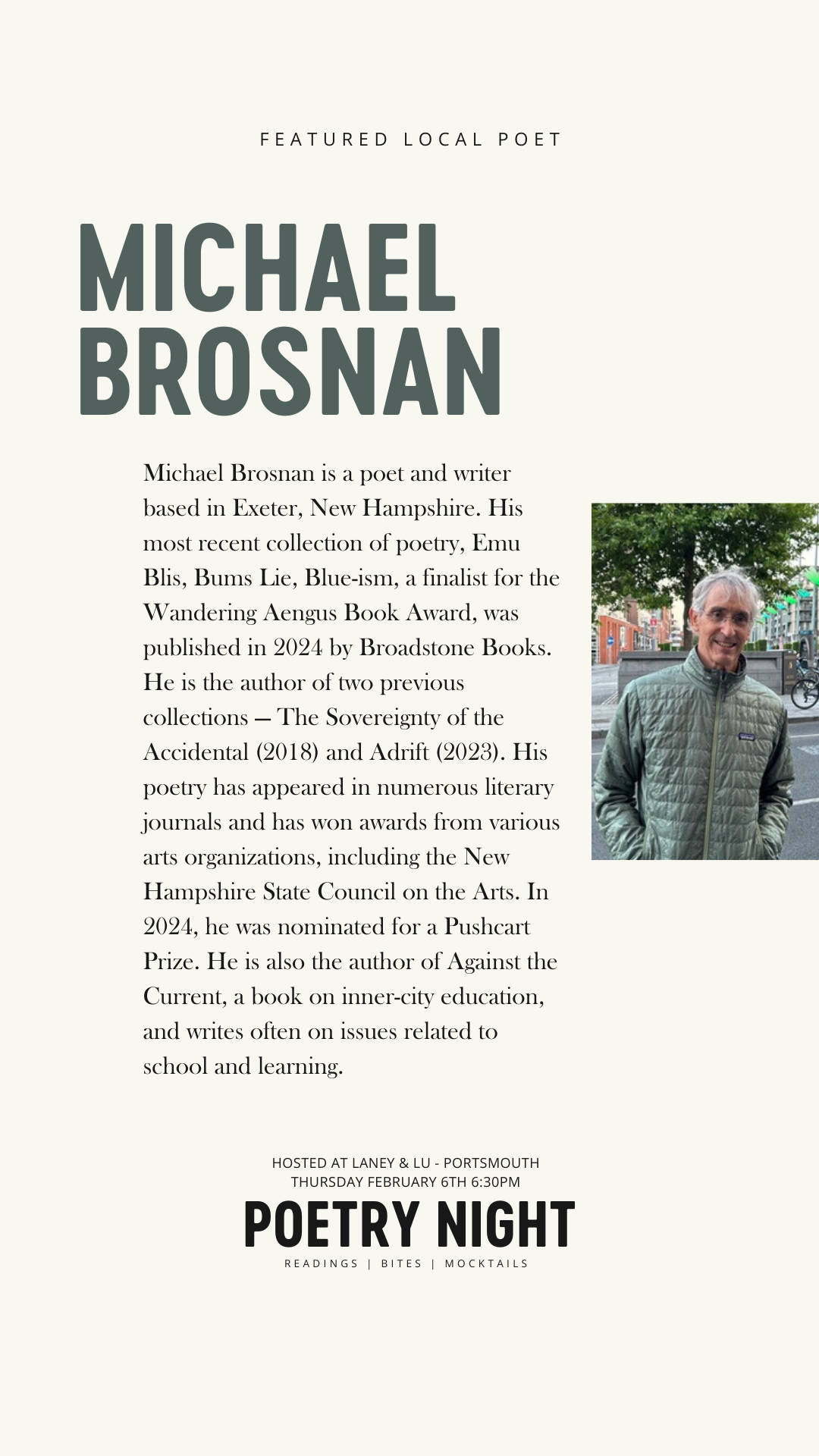

By Michael Brosnan

If you read the March 11, 2025, press release from the U.S. Department of Education, and didn’t know better, you’d think that the recent massive reduction in the department’s staff — from 4,133 to 2,183 workers — was part of a carefully thought-out process to make the department more efficient and effective in support of schools. The language in the release claims that enormous past failures are driving these changes and that reducing the staffing now, with the goal of shuttering the entire department over time, will lead to future gains for children and the nation. We’re to believe that the previous administration, being Democratic (thus incompetent and sinister), created some kind of deep-state departmental bloat that brainwashed American children to embrace liberal causes and wasted taxpayers’ dollars while doing nothing to further academic learning.

On March 20, 2025, the Trump administration followed up the press release with an executive order to close the Department of Education as a means to, as he put it, “enable parents, teachers, and communities to best ensure student success.” As proof of the department’s past failures, the administration points specifically to the poor student performance nationally on the recent National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). A parallel fact sheet offers more “proof” of the departments supposed failures.

In a seeming non sequitur, the executive order also requires that school and college programs receiving any remaining Department of Education funds must stop “advancing DEI or gender ideology.”

If you lean Republican, you might cheer on these cuts — so committed to thinking that what matters most is smaller government and lower taxes. You might buy into the criticisms and rhetoric about reimagined American greatness. You might believe that DEI programs are racist in nature and should be terminated. You may even thrill to the idea of taking down any form of bureaucracy for the sake of conservative principles.

But is the Department of Education really a failed federal program? Does it push political ideology? Will gutting the department improve American education? Will moving its remaining services to other departments improve our government’s effectiveness in serving American families? And will shutting down DEI programs really lead to greater equity and justice in America?

At a recent event at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, a panel of experts with varying political views gathered to discuss such matters. The title of the event: “An Uncertain Future: The U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Policy,” underscores the general concern. While the four panelists had much to say about the Department of Education’s strengths and weakness, and what the future of federal education policy could or should look like, in fact, all were deeply critical of the administration’s efforts and skeptical of its claims. Even Neal McCloskey, director of the Center for Education Freedom at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank that supports the shift of education oversight to the states, couldn’t bring himself to praise the administration. The problem, of course, is that the gutting of the department and the executive order, like other moves of the administration, seem to be an effort to smash things without any clear plans for improving them. They seem primarily driven by ulterior motives and a poorly disguised agenda. Thus, the word “uncertain.”

What has emerged in these early months of Trump’s second term is a clear pattern of shock, disruption, and political retribution on all fronts. It may be that the administration believes that some of these moves — the gutting of governmental offices; the imposing of enormous tariffs that have to date wiped out $1 trillion from the stock market; the abandonment of essential allies; the cozying up to authoritarian rulers; the denial of climate change and undermining of environmental progress; the pulling back of foreign aid that will results in millions of deaths; the arresting and deportation of legal residents without due process; the attacks on higher education with questionable, if not false, claims of antisemitism; the executive orders banning civil rights initiatives; the cuts to NEH funding, etc. — have a valid purpose in serving the greater good. What appears to be happening, instead, is an all-out disruption of American society in a self-serving effort to remake America into two-tier society led and controlled by a small cabal of conservative capitalists, with the rest of us serving as cogs in the machinery of that wealth.

Perhaps it’s too early to tell exactly where Trump is leading us — but from where I stand it looks like we elected Ahab as our president and signed on as the crew of the Pequod.

Much of my professional life has been focused on education — on ways we can improve our systems, support teachers, and offer children curricula that help them thrive. So when I watch the White House tear down a central player in this work, I can’t help but feel alarm, not to mention dismay, frustration, and anger. I know, at the moment, the fate of our public and private education system is not our only concern, and perhaps not the most immediate one. But how we think about education on the federal, state, and local levels — across the entire K-16 spectrum — matters deeply for all of children, not to mention the future of civilization. And the attacks on and mischaracterizations of DEI-related programs reveal a deep disregard for facts and a cynical willingness to hurt institutions that care deeply about academic integrity and educating students for a just, equitable, democratic society.

On the question of funding and taxpayer support, as the panelists at the Harvard event pointed out, the Department of Education is a fairly small department with little impact on our taxes. In terms of saving American citizens money, we could easily fund the work (and more) if we closed loopholes in our tax policies and required billionaires and multi-millionaires to pay their fair share. Researcher Matthew Desmond, in his book Poverty By America, makes it clear that wealthy Americans are currently our major welfare recipients. Over the past four decades, policies created by the rich and favoring the rich have transferred an estimated $50 trillion from the lower and middle classes to the wealthy through enormous tax cuts. The Trump administration plans to increase these welfare benefits for the wealthy. So, one can’t help but ask: If we truly want to save “taxpayers” money, why not start by making the tax system fair? Once we’ve all contributed our fair share, we can then revisit the question of ways to trim our federal government to make it work for the American people without putting undue financial pressure on any citizen and without destroying valuable federal support systems. Starting by decimating the federal government without any consideration for the injustices built into our tax system is either poor management or a deliberate practice aimed at perpetuating or increasing injustice.

For those who care about American democracy, Trump’s plan to dismantle the Department of Education should be viewed with alarm. As panelist Andrew J. Rotherham, cofounder and senior partner at Bellwether, a national nonprofit designed to transform education to ensure equitable outcomes, pointed out, closing the department would mean that schools will lose on average about 8 percent of their annual funding. Poor districts, however, will lose up to 30 percent. So the closing of the department would not only undermine the work of all schools, it would devastate poor communities in all states. Over the course of a few decades, writer Jonathan Kozol has researched and written eloquently about our mistreatment of young people in poor communities. His book, The Shame of the Nation, for one, points out the troubling ways this systemic treatment in schools has been not only deliberate and shameful but also damaging to all of us. Other researchers have also made this point as well. Since then, there has been concerted efforts to address the inequities and close learning gaps based on economics, with its clear link to race. And we’ve made some progress in this area. As Rotherham pointed out, the recent learning gains of Gulf Coast states alone have been worthy of praise and support. Dismantling or closing the Department of Education will hurt these efforts and set us back in time.

Brian Gill, senior fellow at Mathematica, a federally funded research group, added that closing the department will also undermine the essential research on quality education that the department shares with schools. Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency has already cancelled $900 million worth of education research projects. The cuts include U.S. participation in international assessments, the result being that we’ll lose the ability to better understand new directions in teaching and learning or know how our education efforts compare with those of other nations. Overall, we’re also dismantling the infrastructure that supports academic research, making it harder to engage in research in the future.

Catherine Lhamon, former assistant secretary for the Office of Civil Rights in the Department of Education, added that the reductions in staff will undermine essential efforts to protect students’ civil rights in schools. The department’s Office of Civil Rights arose from the 1964 Civil Rights Act and has been working steadily ever since to investigate and address violations. Now the reductions in staff at the Department of Education have led to the closing of seven of the twelve regional offices. In effect, Lhamon said, American children no longer have federal protection from discrimination. “I’m heartsick about it,” she said.

The field of education is highly complex. When the Department of Education was founded by Congress, there was a clear acknowledgment of this fact, with the goal being a federal effort to better support schools and students nationwide. In reality, the department’s efforts to date have been a mixed bag, partly because this work is hard and partly because it is susceptible to the politics of each sitting administration. The No Child Left Behind Act is a case in point. From the time it was implemented in 2002 until 2015, when it was replaced by a system that gave more oversight of outcomes back to the states, the law did result in gains on national standardized test scores, especially among low-income students. On the other hand, its over focus on standardized test as a means to measuring learning progress led to “drill and kill” teaching methods that damaged student interest and engagement. It also pushed aside subjects such as social studies, science, and art. It also played into the hands of wealthy families that could afford extra test-prep help.

The Common Core that followed was an improvement, mostly because it set up guidelines rather than mandates, but it came with its own set of challenges. But giving more control back to the states after 2015, including in Trump’s first term, resulted in lower test scores in math and reading, not to mention highly uneven scores among the states. Of course, other factors were involved in the lower test scores, too — including the increase in immigration, the impact of remote learning during the pandemic, the increased number of students with disabilities, and the continued underfunding of schools in low-income communities. Another factor might be the advent of cellphones, which have damaged the ability for all of us to concentrate.

We could sit here now and claim that the Department of Education has failed in its mission. But I think the better, more honest course of action is to look at the reality in schools, engage in new rounds of research, and try new pathways forward.

Of course, another goal of the Trump administration is to push for more public funding of private education — allowing families to use public money to pay for private school tuitions. This is another area in which the politicizing of a federal department is problematic. I have much to say on this topic, too, but will save it for another day. Suffice it to say that our public educational system is so important to our nation on numerous levels. It deserves our support. Our experiments with charter schools to date have shown us, among other things, just how good our public schools are. Some charters have done well, but most have not measured up. More to the point, we’re better off when we reserve our tax dollars for our public schools only and focus on making them as good as possible. This focus can certainly include ways to give schools more flexibility in response to parents’ needs. But to pretend that privatizing all education is better for the entire nation is to push an illusion that, in the end, plays into the hands of corporations that want to earn money on the backs of children. I have nothing against private, nonprofit schools. But I see no reason our tax money should go to them, except in rare circumstances.

Overall, I think the search for the best role of the federal government in education remains a work-in-progress. But even with the Department of Education’s missteps, there are very few experts who believe the department should be gutted. Three out of the four panelists at the Harvard event, in fact, agreed that it remains essential for, among other things, its oversight of student loans and grants, the funding and disseminating of research designed to improved student experiences and outcomes, and the monitoring of student civil rights, which, prior to the department’s involvement, were widespread, especially for students of color.

Andrew Rotherham made it clear that supporting the department should be a bipartisan matter, since the work impacts schools in all states. He did say, however, that he sees value in rethinking the federal approach to supporting education — aiming for a true partnership with the states. This strikes me as a smart, sensible response to the needs of schools and society. Clearly, it’s not good to have a highly politicized department pushing a partisan agenda — as we’re currently witnessing in the attacks on DEI programs and the removal of highly valuable research funding as punishment. But there are actions and steps a federal department, led by education experts, can take that would be difficult to replicate at the state level — and that make a valuable difference in student experience and outcomes.

What has been missing from our federal approach to supporting education is the independent research I’ve read over the years about specific classroom dynamics and one-on-one interactions that help children learn best. For instance, research from psychologist and educator Joann Deak makes it clear that girls need a combination of competence, confidence, and connectedness to thrive in schools. How we establish those qualities in school matters, yet they are the kind of elements that get pushed aside with a focus on standardized test scores. The research on boys is similar, but one element stands out for me because it’s one that proved to be central to my own learning. For boys, the research says, their relationship with a teacher is central. If they have a connection, if they feel respected and supported, they will engage more willingly and enthusiastically in learning, regardless of the subject. I know this to be true to my experience. I failed Spanish 1 in my high school, then turned around and got an A in Spanish in summer school. The difference? The kindness of the summer school teacher toward me and everyone in the class. It was actually a joy to be there.

Maybe the essential point I’m making is that children need skilled, caring professionals who can help each and every one of them develop their intellectual and social-emotional skills. Creating the classroom dynamics that enable this to happen ought to be central to our federal, state, and local efforts. What our federal office can do is collect and analyze data nationally and share it among the states so that the best of our efforts find their way in to all schools.

Linda McMahon, whose background is in professional entertainment wrestling, not education, describes her job as Secretary of Education as leading the department’s “final mission” to shut the place down. It behooves all of us to resist such dangerous, partisan — not to mention unconstitutional — behavior among our supposed leaders. Eliminating the department and imposing anti-DEI rules and punishing institutions that don’t bend the knee to the administration’s wishes are clearly wrongheaded. They can only damage schools, undermine learning, expose more marginalized students to discrimination, and reduce access to higher education. Such efforts will not improve learning outcomes. But they will make the nation less democratic, damaging our economy and communities in the process.

My mind keeps flashing back to inauguration day in January when Donald Trump did not put his hand on the Bible while repeating the oath of office. It was described in the press as an oversight. But I tend to think it was deliberate — a quiet signal that he wasn’t committing to serving the country; he was committing to serving his own ego and personal financial gain. Maybe I’m reading too much into that moment. What is clear, however, is that America can’t get far with the madness of authoritarian mob-boss leadership. America can only be great if we ensure that our schools, communities, and government are truly democratic and just.

Amid the administration’s bullying ways, I hope we can resist the deceptions, lies, and manipulations and focus on truth-telling. Most people I know approach their work in all fields with honesty and integrity, aiming to accomplish worthy goals. I have no doubt that this is true for the majority of people who work for the U.S. Department of Education, new secretary aside. A strong department, led by experienced, knowledgeable, dedicated educators in service to the real needs of schools in all communities is part and parcel of a valid and valuable plan to ensure that all Americans are prepared for fulfilling lives through both work, family, and citizenship. It’s also how we build a strong, stable economy — and find our way to that more perfect union.