Because I had not read it previously — and because I've heard that it may be Shakespeare's least-admired (if not worst) play, and because I'll actually be in Verona this summer — I decided to read Two Gentlemen of Verona. I'm no Shakespeare scholar, by any stretch of the imagination. In fact, this may be the first time I've written about Shakespeare outside of college. But I felt compelled to write some sort of response — given that the play struck me as more disconcerting than comedic.

I get that Shakespeare scholars would find the play interesting, while making it clear it's not one of Shakespeare's best efforts. Among other things, a number of compelling conceits are tested out here — and then delivered with greater effect in future plays. We get the cross-dressing woman, disguising herself from her clueless boyfriend. We get a wonderful fool — in this case the servant Launce with his incorrigible but well-loved dog, Crab. We get the star-crossed lovers temporarily denied a future by misguided power parents. And don't forget the all's-(sort-of)-well-that-ends-well final act. Friends and lovers reunite. What might have ended in tragedy (see Romeo and Juliet) ends with no bloodletting and plenty of glee.

Also, the word play here is pure Shakespeare. Characters can't simply say hello when meeting; they have to engage in some sort of competitive banter, which, almost independent of the banter itself, is comedic. We also get Shakespeare's deep romantic expressions of love. The head-over-heels stuff.

That said, I couldn't just sit back and enjoy the ride.

The plot primarily involves two supposed gentlemen of Verona — Valentine and Proteus. These young men have been friends since childhood and seem to revere each other. They are both aristocrats, too — so their lives are, relatively speaking, easy. The big question before them at the start of the play is whether they go off to see some of the world (funded by their fathers) or do they stay in Verona. One, Valentine, is excited to leave. The other, Proteus, is more interested in staying put so he can woo the young Julia. But through a backfiring act of his own deception, Proteus is sent by his father to join Valentine in a not-so-far-flung corner of Italy.

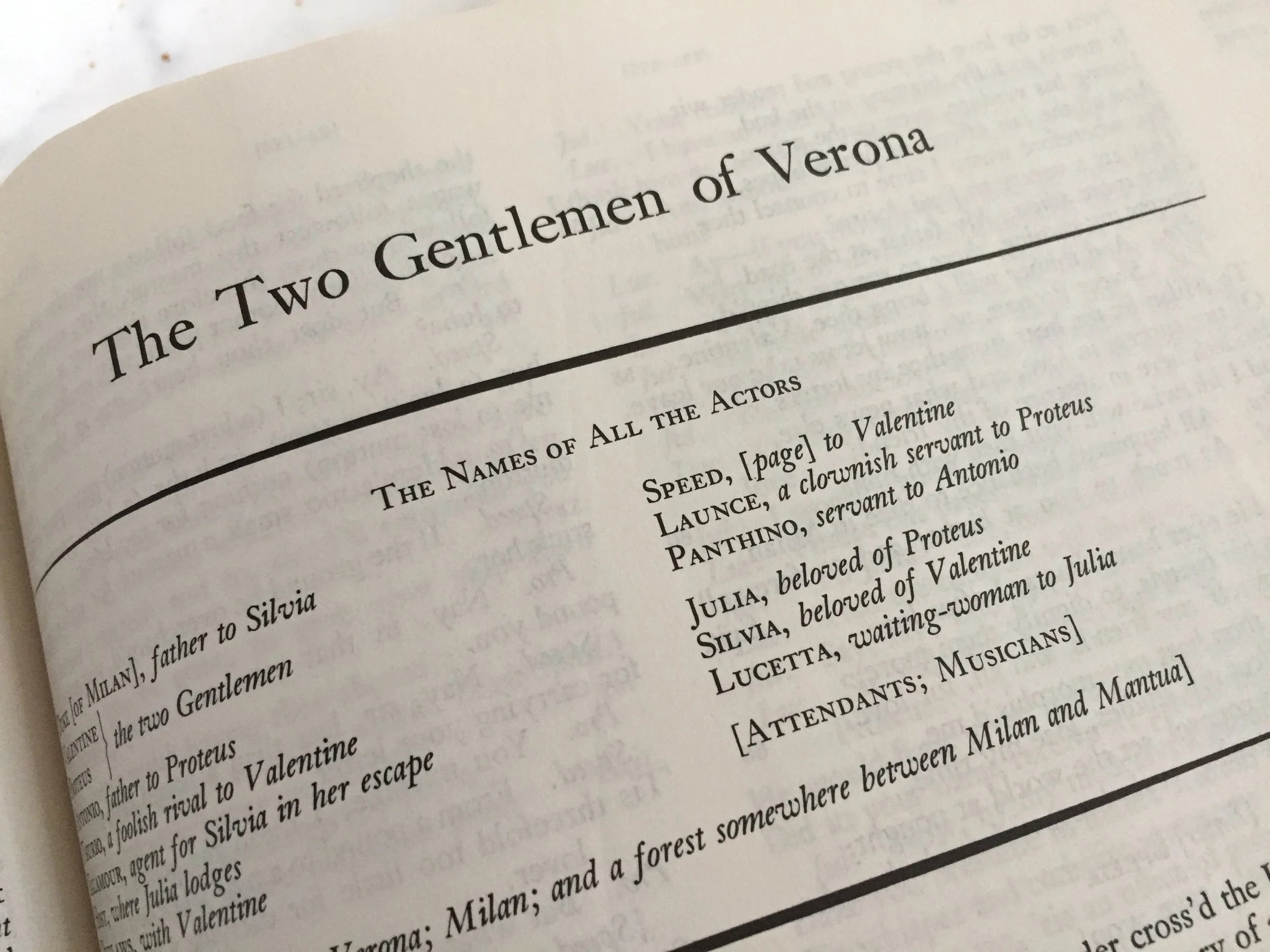

Why did I keep frowning at my ten-pound edition of the complete works of Shakespeare as I read? Mostly, I found it hard to stomach Proteus. This supposed friend of Valentine, this supposed gentleman of Verona, sets out to deceive, manipulate, and hurt just about everyone in the play. There's a disturbing level of deep-seated entitlement in the fella.

Basically, Proteus decides he is no longer in love with Julia — the bright and beautiful woman he adored a day ago — and sets to pursue the love of Sylvia, who happens to pine for Valentine and whom Valentine clearly desires. To "win" Sylvia, Proteus deceives his own father. He breaks Julia's heart. He not only tricks Valentine, but actively plots to sell him out — get him banished from Milan. Proteus also deceives Sylvia's father, The Duke — convincing him to send Valentine away — while he pretends to help convince Sylvia to accept the hand of another suitor, the wealthy, honorable, and quite dull Thurio. Basically, Proteus is an untrustworthy creep. A man with no moral compass (thus, the protean name). He even admits to himself that he's a jerk, when he "slander[s] Valentine/ with falsehoods, cowardice, and poor descent."

In the end, Proteus almost succeeds in this bold love-grab, except for one problem: Sylvia would rather be eaten by a bear than to accept Proteus's love. She sees him for what he is: a liar, a deceiver, a conniving cheat. In the last act, Proteus, deeply frustrated by Sylvia's repeated rejection, basically decides it's time to force himself on her — as if that somehow translates into a compelling love bond. Some critics say Proteus is threatening rape in this scene. But given that there are other people around at the time, it strikes me that he'll be OK with unwanted groping.

How is this remotely comedic?

I suppose the answer is one of timing. Proteus pulls back from all his bad behavior in one quick moment — when Valentine arrives on the scene and sees his supposed friend attempting to brutalize the woman he loves. Valentine, as one might expect, is outraged and hurt. Says their friendship is toast.

But... then things get weird. Proteus, caught in his ego-driven plot, decides to apologize semi-profusely. He says he doesn't know what came over him. He now sees that he is wrong. He claims his friendship with Valentine means more than anything.

Does Valentine buy this groveling? Hook, line, and sinker. He not only takes Proteus back as a friend — he may even have offered to give Sylvia to Proteus as a sign of friendship. This, of course, is a point of deep contention among critics. Did he just say Proteus can have Sylvia or did he awkwardly say that he still loves Proteus as a friend?

You can judge. Valentine's rhyming couplet read: "And, that my love may appear plain and free,/ All that was mine in Silvia I give thee."

I have to assume Valentine is not trying to offer up Sylvia as a prize for renewed friendship. That's not only creepy, it makes zero sense. Still, if I were Sylvia, and I heard the man I loved so quickly forgive the Lothario who just tried to ruin everyone's lives, then force himself on me, I'd be miffed at my boyfriend. In fact, I think I'd have second thoughts on the whole love thing. What do I really know about Valentine, I'd wonder. And would the jerkhead Proteus keeping coming around — you know, as a friend and maybe a drinking buddy to Valentine?

To me, the most telling part of the final act is not what the characters say to cheer us up for the trip home. It's that Sylvia, previously outspoken in all instances, says absolutely nothing.

My guess is she is quietly seething, or perhaps stunned by the macho reunion. I also imagine that, after the action in the play, she'll take her father aside and say, "Let's start over. I think I can do better than any of these gentlemen."